Objective: Expressing or dealing with facts or conditions as perceived without distortion by personal feelings, prejudices, or interpretations (Merriam-Webster)

Objective: Expressing or dealing with facts or conditions as perceived without distortion by personal feelings, prejudices, or interpretations (Merriam-Webster)

I responded to a discussion thread on ProjectManagement.com this week about categorizing risks and after doing so, I spent some time thinking about the impacts of bias on how we evaluate risks.

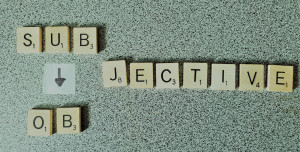

While subjectivity affects all aspects of delivery, when we evaluate risks, these impacts can get compounded through the combination of the intrinsic uncertainty of risks with our own biases. And if we think about a department or enterprise portfolio with each team perceiving risks through their own biased lenses, there will be very little precision to support a portfolio-level evaluation of risk.

Tailoring risk management to fit the context of a given project means that we may not always capture the same information, but at a bare minimum, we usually have a risk description, impact and probability.

How could we become more objective in stating or evaluating these?

There is no need for us to become template zombies by imposing “if-then” or other rigid format to how risks are described. What is important is to clearly articulate the uncertain event as well as the impact to the project. We should try to be as specific as possible with regards to the event and, ideally, time box it. This will help us both in getting the attention needed from risk owners, designing effective risk responses, and being efficient about use of buffers and contingency reserves. Whereas “If we lose a team member, our timelines will be impacted” is not particularly effective, “If we lose a business analyst during the first month of the project, it will delay the project on a day-for-day basis” provides greater clarity and focus.

While we will usually restrict quantitative analysis to higher criticality risks, if we provide thresholds for assigning qualitative impact values (e.g. high, medium, low), we can help teams to get more objective. For a frugal stakeholder, a $1,000 cost overrun might seem high. But if we have threshold guidance which states that negative cost variances under $5,000 and which are under 5% of a project’s total budget should be considered to be low impact, they will be less likely to let their own biases skew their evaluations.

If the project in question is very similar to others we have done in the past, risk evaluators could ask the question “How frequently was this risk realized in the past?“. But in many cases we don’t have the benefit of good historical data to substantiate our evaluation and the current project may be sufficiently different to make it impossible for us to look in the rear view mirror. The only way in which we could get more objective is to involve a sufficiently diverse group of stakeholders utilizing Delphi or similar methods to reduce the impacts of external bias.

Increasing the objectivity of how we analyze risks could help us to become more precise, which might then help us over time to improve the effectiveness of our risk management practices.